Prometheus: the eternal illusion

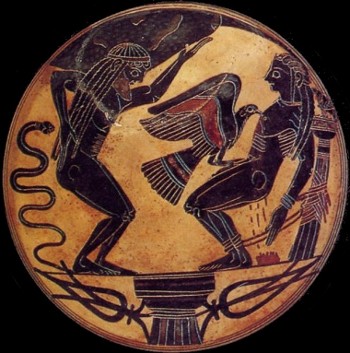

The myth tells us that Prometheus is the progenitor of mankind. Foreseeing how the revolt of the Titans would end, he preferred to side with Zeus and looked away from the purpose to destroy the entire human race. As a result, however, of the deception of the bull perpetrated by Prometheus in favor of men, Zeus punished him by depriving them of fire.

In this brief article I will omit the interesting philosophical aspects that recognize this loss of fire as a convenient return to an initial status for mankind (see G. Lampis – La nascita dell’uomo –Mythos), but let’s continue through the myth. Following this action from Zeus, Prometheus secretly entered Olympus, lit a torch from the blazing chariot of the Sun and broke off a burning ember that gave back to the men.

In this brief article I will omit the interesting philosophical aspects that recognize this loss of fire as a convenient return to an initial status for mankind (see G. Lampis – La nascita dell’uomo –Mythos), but let’s continue through the myth. Following this action from Zeus, Prometheus secretly entered Olympus, lit a torch from the blazing chariot of the Sun and broke off a burning ember that gave back to the men.

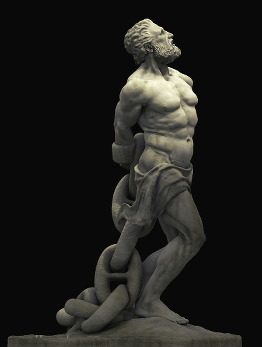

Zeus swore revenge: he bound Prometheus, naked, at a peak of the Caucasus, where a greedy vulture devoured his liver all day, one year after another. And his agony did not end, because every night (while suffering the pangs of cold) the liver grew back.

Giving fire to men was a gesture by which Prometheus wanted to enable them to independently manipulate and adapt things to their needs, to become capable of governing. In other words he had made them gift of the technique. Man was given thus the technical expertise needed to have an easier life, but the myth of Prometheus reminds us that the gift is always a deception, that the gift not only frees but also obliges, that it confers but at the same time it subtracts.

Without the support of a privileged knowledge, the technique is in fact an instrument that just because it offers new opportunities, it hides many pitfalls. And those pitfalls are potentially as destructive for the survival of humanity as the progress that the technique guarantees appears limitless. It contains the promise of a simple happiness and the abolition of fatigue and pain – then of sacrifice – without having to go through the stages of the creative process and therefore, regardless of the knowledge and wisdom.

I remember how, in the ancient traditions, the technique was always considered to be related to the sphere of the sacred and therefore generally belonged to a religious leader or the shaman, who overcame the considerable tests necessary to acquire the knowledge with which to manage the huge potential of the action. The centrality of technique in the modern world was born after the death of the fundamental question of the meaning of human life and it has developed in the Promethean illusion of being able to take possession of things and to adapt the world to our needs.

The action is always full of a dual aspect potential and it inevitably includes also possible dangerous drifts. The extraordinary power of the technique easily acquired by those who do not meet the required knowledge, can lead to a feeling of omnipotence, apparently opening the doors to the sky; but it can also suck in a dangerous spiral without end.

The availability to simply buy the technical solution at the market, without having traveled the long and arduous process of initiation that gives the necessary accompanying virtues, can open to the risk to confuse our momentary well-being or the satisfaction of the immediate need, forgetting the wider horizon where the law of the Whole transcends the individual.

In other words, the indiscriminate access of the technique to any level delivers a cheap opioid illusion of being able to remove the dialogue with the mystery of life, always linked to the mystery of death.

The more the technical acquired skill, the more the need for an intense reflection and for the achievement of a deeper awareness that leads to repair the breach that the technique itself risks to operate at universal level.

And what easy and persuasive promise the indiscriminate mass production of the technique can offer, if it is not the one from Mephistopheles in Goethe’s Faust?

Among ‘the greats’, I’m second-class:

But if you, in my company,

Your path through life would wend,

I’ll willingly condescend

To serve you, as we go.

I’m your man, and so,

If it suits you of course,

I’m your slave: I’m yours!

….

With such treasures I can truly serve you.

Still, my good friend, a time may come, 1690

When one prefers to eat what’s good in peace.

Faust gives up to take the difficult path that expresses all the creative possibilities of man and he tried to accept what is immediately offered, while realizing that it will be “… a never-satiating food, restless gold, a slew of quicksilver, melting in the hand, games whose prize no man can land….And honour’s fine and godlike charm, that, like a meteor, dies?… fruits then that rot, before they’re ready“.

Moreover, the technique also shows an aspect of a hierarchical and aristocratic nature, it conditions and prepares – that is – the social organization and determines the actual order (see. G. Lampis – L’arte della politica al tramonto della modernità –Mythos 1994).

Moreover, the technique also shows an aspect of a hierarchical and aristocratic nature, it conditions and prepares – that is – the social organization and determines the actual order (see. G. Lampis – L’arte della politica al tramonto della modernità –Mythos 1994).

Here the Promethean illusion can take shape and expand itself: the chimerical attempt to remove the technique from the “control of Gods”, depersonalizing its distribution and popularizing its content.

The immense strength of the technique continues to show to this day constantly in conflict between people who hold its keys and are able to industrialize it and those that seem to only suffer its negative effects.

“But the technique can not contradict his aristocratic nature; if it is available to the mass there must be an hidden reason to explore. It seems that the technique, to fulfill his destiny, must undergo a masking” (G. Lampis, op.cit.)